Contracts - what are they for? Winning a battle in court, or running a successful project?

Now that new contract management technology is demanding clarity, structure and contracts that can actually be read, could the days of voluminous small print be over? Find out about Next Generation contracts, and how to get started.

Dr Rob Waller, Director of the Simplification Centre, and President Elect of the International Institute for Information Design.

Dr Helena Haapio, contracts lawyer and Associate Professor of Business Law, University of Vaasa, Finland, and director of Lexpert Ltd.

Stefania Passera, legal information designer and soon-to-be Doctor of Science (August 2017) at Aalto University, Helsinki.

Contracts - what are they for? Winning a battle in court, or running a successful project?

Someone once wrote: “I apologize for writing such a long letter, but I didn’t have time to write a short one.”1

There’s no doubt about it - to simplify a contract takes time, and because most are so complex that’s in short supply. Moving from complex to clear requires a new approach, creative skill and effort, persuasion and negotiation. And there’s bound to be opposition, mostly well-meant, because of concern about risk and change.

So when we come across a clause no one knows the origin of, or the reason for, isn’t it easier just to carry on?

Time to bring contract clarity to the mainstream

IACCM has been campaigning about clarity in contracts for quite a few years now. We can think of many outspoken blog posts by Tim Cummins, well-attended webinars and conference sessions, and the IACCM Contract Design Assessment Program.2

As Tim put it: “Impenetrable, incomprehensible, confusing and downright boring. These are a few of the words commonly associated with contracts. Whether it is the way they are designed, or the way they are worded, the overwhelming majority of contracts merit those descriptions.”3

At the recent IACCM Europe Conference in Dublin you could get the impression from the program that contract simplification had faded as an issue. Unlike equivalent meetings over the past few years in London, Copenhagen and Rome, there was little explicit mention of it in the title of any of the sessions. You’d be wrong.

Far from ignoring it, numerous speakers just took it for granted that contracts need to be simpler, based on tech-enabled standardization, and trusted relationships. Clarity is an important component of IACCM’s Ten Pitfalls to Avoid.4 A speaker from a global company mused about whether we could do without contracts: delegates with a legal background felt compelled to distance themselves from the bad guys still defending the small print. It felt like the contracting paradigm is shifting.

It may be time for contract simplification to move from the experimental to the mainstream, and to move towards an agreed model of what a clear contract looks like.

The problem: contracts focused on winning disputes, not preventing them

In the distant past, business was based largely on trusting relationships. But in an increasingly litigious society, most business transactions are now based on complex contracts. The problem is that they are largely incomprehensible by people without a legal background, and the absence of clarity makes them open to disputed interpretations by lawyers.

Traditional lawyers and law teachers tend to focus on contract law, not contracts themselves, the deal the parties wish to do, or the business relationship they wish to develop. They are focused on winning possible future disputes and litigation, rather than preventing them in the first place. They pay little attention to the strengths and successes of good contracts, and to the role they might play in running successful projects.

The new paradigm - we call it Next Generation Contracts5 - is proactive and positive: As one of us has written: “A proactive contract is crafted for the parties, especially the people in charge of its implementation in the field - not for a judge to decide about the parties’ failures. Instead of providing the most advantageous solution for one of the parties, in case the other fails to comply with its contractual obligations, the proactive contracting process and documents seek to align and express the interests of both sides, in order to create value for both.”6

Another writer has likened proactive lawyers to engineers: “Like engineers, transactional and legislative lawyers want to make something useful that works for their clients.”7

What’s changing? New approaches to old problems

Below we contrast the old approach with the new. On the left, encyclopedic content, aimed at ensuring no risk is uncovered, no topic ignored. On the right, the focus is usability, action, clarity and value - and a contract designed to be read by everyone who needs to use it.

Table 1: Moving to Next Generation Contracts

|

From this

|

… to this

|

|

Legally perfect contracts that prepare for failure and seek to allocate all risk to the other party.

|

Simple usable contracts that facilitate and guide desired action and help manage change.

|

|

Contracts are legal tools, made to win in court: legally binding, enforceable, must cover all conceivable contingencies.

|

Contracts are business tools, made for action and communication: must be clear, understandable, easy-to-use to achieve business goals for a win-win deal.

|

|

Contracts allocate risk. They are needed only when things go wrong.

|

Contracts add value. They enable business success and prevent problems and disputes.

|

If contracts are to be usable, then we must ask who the users are, and what they need to achieve. And we must design the contract documentation so it is clear and can be easily understood by those people:

- Sales people on one side, and purchasers on the other

because the contract may modify what has been stated in sales documents or conversations;

- Operational people

for the supply of the goods or services to be carried out properly. This might include instructions and standards for delivery, inspection, packing, and invoicing;

- Managers

so the parties’ suppliers have the right processes, permissions, safety standards and insurances in place.

Next Generation contracts do not ignore risk, and still include sections which address possible future events, such as disputes or force majeure. But these are separated from the practical information needed to manage the contract.

New Generation contract design - what’s different?

First, to be understandable and usable, a contract needs to fulfil some basic design requirements:

In a document designed to be read the language must be clear, and the type large enough to read. Many contracts immediately fail this test.

- There must be an access structure

Complex information is not read in the same way as a newspaper or a novel. Effective readers of complex text read strategically, in a purposeful way to solve problems. They skim-read to see the structure, re-read parts they don’t understand, follow up cross references, and compare information from different documents (for example, sales promises with contractual conditions). This means that contracts must have an access structure, with headings logically organized and visible at a glance. A good structure helps users to search, find, and interpret information.

Visualisation: beyond basic design

Think of the best user manuals you have used, the best illustrated textbooks or travel guides. The designers and writers of these document types are focused on the user as well as the content, and the structure will have evolved over time, to the fully illustrated, structured and usable formats we are all familiar with.

These documents use visualization at a number of levels - structuring text through layout, and supplementing it with tables, explanation panels, lists, charts, maps and pictures - whatever it takes to explain the content effectively.

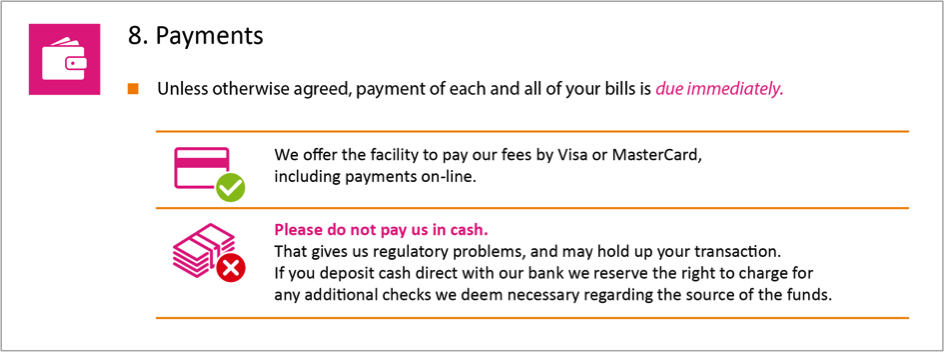

Below we see some examples showing how customer-oriented firms can take advantage of visualization in contracts. Figures 1-3 are from the terms and conditions of a UK-based law firm, Coffin Mew, designed by Stefania Passera (shown here by permission).

In Figure 1 below, icons are used to indicate the start of the section, and its topic. Correct and incorrect options are instantly recognized through symbols: green + tick for correct, red + cross for incorrect. Icons, color, bullets and horizontal dividing lines articulate the text structure, acting as an extension of usual punctuation.

Figure 1

Figure 2 below uses a side-by-side layout to juxtapose the equivalent rights of the customer and the firm. This makes them easy to compare, and the layout also accords equivalent respect to the two parties in the relationship.

Figure 2

Figure 3 below shows how certain types of information are much better explained in chart form - for example, processes and conditional text.

Figure 3

Contracts can become even more visual - for instance, diagrams such as timelines, flowcharts, and swimlane charts can be used to further clarify complex information and present it in more actionable formats.8

Visual communication is even more important when users have literacy problems. Robert de Rooy recently received an IACCM Innovation Award for his work on comic contracts for fruit pickers in South Africa.9

Simplification - what it is and what it is not

Below we counter some common myths and misunderstandings:

There is no ideal length for a contract. A one-page contract might sound like something to boast about, but not if brevity is achieved at the expense of adequate information, legibility or clarity. ‘One page’ contracts sometimes turn out to be many more pages if printed in a font size you can read comfortably.

Plain English can actually extend the length of a document, because jargon has to be explained. Vijay Bhatia, an expert on legal writing, talks about ‘easification’ - explanations added to legal texts to help readers understand.10 Design theorist Per Mollerup distinguishes between two kinds of simplicity. Quantity-simple things have fewer surface features and look visually simple, but may actually be harder to use because they give us so little help. In contrast, we prefer quality-simple, prioritizing the simplicity of the user experience.11

- It’s just pretty pictures

Is better contract design just a matter of making contracts look nice? Emphatically not. Experimental studies show that visually designed text not only improves the speed with which people find the answers to questions, but accuracy too.12 And there is also evidence that when people like the look of an interface, they also feel it is more usable.13

This is a frequent criticism of simplification. It emerges in several ways: contract drafting experts who say there is no other way to express the same content as accurately, complex language is just a tool of their trade; others who consider it rude to treat the reader as if like a child, explaining everything in short words. Our experience is that people are more often delighted than insulted when presented with clear information. Clarity is actually good manners. In the case of contracts to be made or implemented by non-experts (including consumers and employees), we surely do not want them to have to rely on documents that they don’t understand.

As we said at the beginning of this article, moving from complex to clear requires a new approach, creative skill and effort, persuasion and negotiation. All change processes require focus, effort and commitment if they are to be successful.

How to get started with contract simplification

Information design and visualization offer a variety of new solutions and patterns to simplify contracts.14 However, what you do and how you do it will depend on your goal.

There’s no one way to run a contract simplification project, as it depends so much on the size of the organization, its management style and attitude to risk, and the degree of transformation needed. At the most basic level, simplification could just be the application of plain language and clear design to existing documents, paying attention to the language and the tone of voice in which you address your contracting partner. Or you may want to tackle the information architecture and layout of your contracts - reorganizing the key terms, creating summaries, or giving visual cues that help users find the information they need.

You can bring in specialist consultants, or involve in-house designers or technical writers if you have them in your organization. Your first step might be to develop a prototype of what a simpler contract could look and feel like - or some sample clauses to begin with. More radical projects often involve strategic change to procurement and sales processes, so tend to need larger project teams, creative workshops and user consultations.

Whatever the scale of your project, it’s important to recognize that you are running a change process: your chances of success will be much improved with a senior champion to support you, and close involvement of key stakeholders.

This article is based on a webinar from 16 June 2016 - you can download the slides and listen to the webinar online: https://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=9305

End notes

- Ascribed to numerous people, including Cicero, Pascal, Locke and Luther. See http://quoteinvestigator.com/2012/04/28/shorter-letter/

- http://www.iaccm.com/contract-design-assessment. For the Contract Design Award Program, see also http://www.iaccm.com/contract-design-award-program.

- Tim Cummins, Can contracts really change? IACCM blog post, 2 March 2016. Accessed 15 May 2017 from https://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=9147.

- Tim Cummins and Jonathan Dutton, The 10 critical pitfalls of modern contract management, webinar recording & white paper, 16 March 2016. Downloadable from https://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=9150.

- Helena Haapio, Next Generation Contracts. Doctoral dissertation, University of Vaasa. Lexpert Ltd 2013.

- Gerlinde Berger-Walliser, Robert C. Bird and Helena Haapio, Promoting Business Success through Contract Visualization. Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, Vol. 17, Winter 2011, p. 55-75, at p. 61.

- David Howarth, Law as Engineering, Thinking About What Lawyers Do. Edward Elgar 2013, p. 67.

- Stefania Passera, Flowcharts, swimlanes, and timelines - Alternatives to prose in communicating legal-bureaucratic instructions to civil servants. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, forthcoming. Available at https://stefaniapassera.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/jbtc_submission.pdf.

- See, for example, Kate Vitasek, Comic Contracts: A Novel Approach To Contract Clarity And Accessibility. Forbes, 14 February 2017, http://tinyurl.com/hcfdtna or visit Creative Contracts website at www.creative-contracts.com

- Vijay K. Bhatia, Simplification v. easification - the case of legal texts. Applied Linguistics, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1983, p. 42-54.

- Per Mollerup, Simplicity: a matter of design. BIS Publishers 2015.

- Stefania Passera, Anne Kankaanranta and Leena Louhiala-Salminen, Diagrams in Contracts: Fostering Understanding in Global Business Communication. IEEE Transactions of Professional Communication. Vol. 60, No. 2, 2017, p.118-146.

- Noam Tractinsky, Adi Shoval-Katz and Drori Ikar, What Is Beautiful Is Usable. Interacting with Computers, Vol. 13, Issue 2, December 2000, p. 127-145.

- Rob Waller, Jenny Waller, Helena Haapio, Gary Crag and Sandi Morrisseau, Cooperation through Clarity: Designing Simplified Contracts. Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, Vol. 2, Issue 1-2, March/June 2016, p. 48-68; Helena Haapio and Stefania Passera, Contracts as Interfaces: Exploring Visual Representation Patterns in Contract Design. In: Daniel M. Katz et al. (eds.) Legal Informatics. Cambridge University Press, forthcoming; and Contract Design Pattern Library, http://www.contractpatterns.design.

About the authors

Dr Rob Waller is an experienced practitioner, teacher and theorist of information design. He consults on contract simplification, coordinates the Simplification Centre, a UK non-profit which advocates plain language and clear design, and is President Elect of the International Institute for Information Design.

Dr Helena Haapio is a contracts lawyer and a leading advocate of proactive approaches to contract design. She is Associate Professor of Business Law, University of Vaasa, Finland, and director of Lexpert Ltd. She is a Fellow and Advisory Board member of the IACCM.

Stefania Passera is a legal information designer, and soon-to-be Doctor of Science (August 2017, Aalto University, Helsinki) specialising in the design and visualisation of business contracts. She is the initiator of Legal Design Jam, where lawyers, designers and business people work together to visualise legal contracts. She is a IACCM member and the Finnish Representative of the International Institute for Information Design.

{{cta('c282a356-5120-4b12-b94b-0eb0e425ee28','justifycenter')}}

Return